15 Oct Hospital infections: the effects on the health facility

Edited by Dr. Maurizio Alberto Gallieni, Associate Professor of Nephrology at the University of Milan.

Since 2018 Director of the Complex Operational Unit of Nephrology and Dialysis of the ASST (Local healthcare area) Fatebenefratelli Sacco of Milan.

Author of over 200 scientific publications, indexed in the PubMed database of the National Library of Medicine.

He is a member of various Scientific Societies, also has coordination positions and is the Editor for Italian and foreign journals of Nephrology.

The risk of healthcare associated infections exists both in hospital and in out-of-hospital settings and is increasing dangerously.

The number of HAI associated fatalities is worrying.

Health institutions do not hide this fact and for some time they have launched a zero tolerance program against infections, promoting a certain level of hygiene and safety.

In his article, Prof. Gallieni explains what the effects of an infection are on hospitals and reminds us that prevention is the best weapon we have at our disposal.

The prevention and adequate treatment of infections, in particular those from CVC, is part of the objectives of the zero tolerance program for infections in health facilities.

For some time, especially in the field of intensive care, there has been talk of “zero infections target”, but this concept has now extended to all areas of care, since infections related to care practices increase morbidity and mortality, as well as care costs.

Many protocols have been developed on the appropriate use of antibiotics to avoid both the inadequate treatment of an infection and their frequent and unjustified use, which causes the problem of antimicrobial resistance.

In addition to care, the protocols focus on prevention, which is the best course of action.

Although preventive protocols have a cost, preventing of a single case of septicaemia results in significant savings because it avoids prolonged hospitalization, reduces the cost of treatment and can obviously avoid suffering and complications, which may be very serious for the patients.

The Quality and Safety Research group of Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, USA) proposed a model of good practices and behaviour for the prevention of hospital infections that takes four practical approaches:

Raise awareness among healthcare personnel about the serious risks associated with CVC infections and the importance of preventing them.

Educate and train health personnel to adopt the guidelines and recommendations indicated by scientific societies.

Implement the procedures learnt and agreed on in the education stage, standardizing the methods of care, using checklists and creating a vascular access support team.

Monitor hospital infections by doing specific surveys, implementing a tracking system and assessing how they are approached and controlled (learn from mistakes).

Estimated costs and management time for an infection

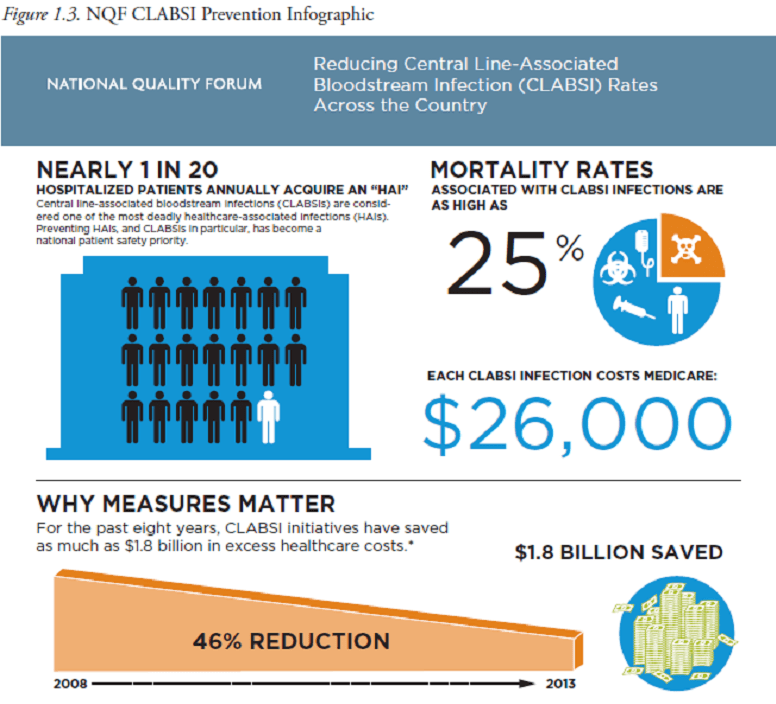

About 5% of hospitalized patients, i.e. 1 in 20, develop nosocomial infections. Among these, septicaemia associated with vascular access are some of the most dangerous, with a mortality rate of 25%.

Each episode of CVC-related infection significantly increases costs.

An Italian study (Tarricone 2010) conducted in intensive care departments indicated a doubling of the average cost of hospitalization (then € 18,241 and € 9,087) and an increase in the average hospital stay from 8.5 to 17.4 days.

An American study (Stone 2005) estimated that each case of CVC-related infection increases the length of stay from 7 to 21 days and increases the cost by approximately $ 37,000 per patient.

How can you prevent infection?

The prevention of CVC-related infections should be carried out at all levels of the care process: from insertion to the use and maintenance of the catheter.

Effective prevention must take into account all possible ways that the CVC or the solutions that are injected through the catheter can become contaminated.

In particular, both the intraluminal and extraluminal routes can be used by microorganisms to enter the body and cause infection.

Most catheter infections occur 5 days after insertion, indicating the importance of a very careful preventive approach not only at the time of insertion but also during the subsequent phases CVC use.

In 2009, Shapey et al. evaluated CVC management methods in a tertiary hospital, finding shortcomings in 45% of post-insertion management events, especially when using exit-site caps and dressings.

This study was a stimulus to providing more training of healthcare personnel and the practice of self-checking procedures.

The use of a CVC care bundle, a shortlist of essential tasks to follow in the care of patients with CVCs, has proven effective in patients admitted to intensive care units and is also being extended to dialysis centres.

Infections from extraluminal contamination can be prevented with adequate antisepsis at the time of catheter insertion and with careful nursing practices when applying and renewing dressings, especially if antimicrobial materials are used.