15 Oct WHEN SHOULD A VENOUS VASCULAR ACCESS BE USED?

Edited by Dr. Maurizio Alberto Gallieni, Associate Professor of Nephrology at the University of Milan. Since 2018 Director of the Complex Operational Unit of Nephrology and Dialysis of the ASST (Local healthcare area) Fatebenefratelli Sacco of Milan. Author of over 200 scientific publications, indexed in the PubMed database of the National Library of Medicine. He is a member of various Scientific Societies, also has coordination positions and is the Editor for Italian and foreign journals of Nephrology.

Before talking about dialysis, you need to know that this therapy requires a venous vascular access to be created in order to carry out the treatment. As Prof. Gallieni clearly explains in this article, a venous vascular access is not only for those who undergo haemodialysis. There are several pathologies that require a venous vascular access and different types of accesses are available, according to the disorder to be treated. These are delicate areas, because of the high possibility of infection, and they shouldn’t be underestimated.

Several pathologies require a peripheral or central venous access in order to be treated. For example, the infusion of antibiotics when treating infections that cannot be cured with antibiotics administered via other routes, chemotherapy treatments, which normally require a central venous catheter, parenteral nutrition and many of the therapies performed in intensive care units; acute and chronic extra corporeal purification therapies, including haemophiliacs, which is currently used on about 42,000 patients in Italy. For patients undergoing haemodialysis, the first choice access is arteriovenous, i.e. a fistula or vascular prosthesis, which has the advantage of being able to insert needles that are removed at the end of each session.

However, in approximately 30% of patients, dialysis is performed using a central venous catheter (CVC). If on one hand, venous accesses are essential for the treatment of many disorders, on the other hand the possible complications are nevertheless significant and potentially dangerous. The main complications include infections and thrombosis.

VENOUS VASCULAR ACCESSES: WHICH TYPES ARE THERE AND WHICH SHOULD I CHOOSE?

There are many types of venous vascular accesses. The choice of access depends on the pathology that requires it.

An important distinction should be made between peripheral vascular accesses and central vascular accesses.

Venous cannula used for peripheral accesses can cause local infections, called phlebitis, which in some cases can become serious systemic infections. The entry of bacteria through a central vascular access often leads to bacteraemia that can lead to a systemic infection or septicaemia. CVCs, or central venous catheters, have different characteristics according to their use. For example, in the field of oncology, large suction blood flows are not required unless when carrying out blood sampling, while a vascular access that allows the administration of chemotherapy in a central vein it is very important in order to prevent the toxicity of the pharmaceuticals coming into contact with the peripheral venous wall. Totally implanted catheters, called PORT, are widely used when prolonged therapies are required because they have the great advantage of reducing infections.

Haemodialysis patients on the other hand require higher blood flows and fully implantable catheters have not been as successful. CVCs for dialysis are implanted percutaneously and have an exit-site that can be near the point at which the catheter enters the vein, i.e. at the insertion point of the CVC, or the exit-site can be further away from the insertion point of the CVC into the vein, which is prepared by creating a subcutaneous path or tunnel. Central venous catheters are referred to as being tunnelled or non-tunnelled according to their proximity to the exit-site.

Since tunnelled CVCs are often used for months or years, CVCs are also often referred to as being “permanent” or “temporary”.

However, this distinction is misleading because CVCs should be used for the shortest possible time and even tunnelled CVCs can be temporary, until an arteriovenous access has been established, unless this is not feasible or there are contraindications.

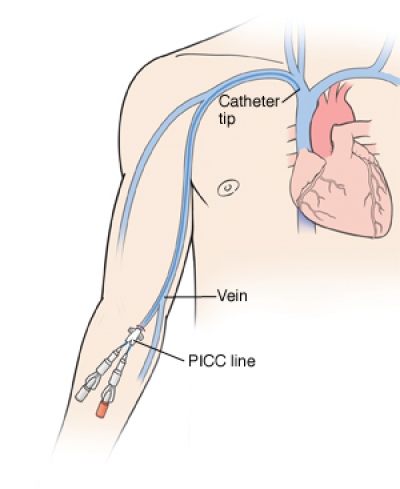

Lastly, there are also peripherally inserted central catheters PICC used outside the field of dialysis, which can be inserted with by nurses using echo-guidance techniques.

Regardless of the type of access, all percutaneous, peripheral and central venous accesses require the periodic application of dressings that protect it from local or systemic infections.